Your garden is no place for critters. You may enjoy a leisurely stroll with the family cat, but you won't be amused with his leavings. Dogs can trample a seed-bed faster than anything short of the neighbor's children, especially if you are out walking with the cat. Wild animals from deer to raccoon can do even more damage, because they are intentionally after your produce.

Your garden is no place for critters. You may enjoy a leisurely stroll with the family cat, but you won't be amused with his leavings. Dogs can trample a seed-bed faster than anything short of the neighbor's children, especially if you are out walking with the cat. Wild animals from deer to raccoon can do even more damage, because they are intentionally after your produce. The most effective way to keep wayward wildlife from your garden is to erect a fence. Fencing materials are certainly not cheap, but a well-constructed fence will serve for years. Woven wire, poultry netting, or welded wire will keep out most neighborhood pets and pests. The bottom of the wire should be buried below soil level if rabbits are a problem. Foil persistent gophers by lining planting beds with fine mesh fencing. A fence up to 8 feet high is necessary to prevent deer from jumping over. Leave approximately the top 18 inches of the wire unattached to any support. This wobbly fence discourages such climbing critters as raccoon, porcupine, and opossum.

In lieu of expensive fencing you may first want to try some of the many intriguing animal repellents available. Forget the store-bought solutions and whip up your own thrifty alternatives. Here are a few suggestions:

® Hair clippings from the local barbershop scattered around the garden scare off critters that fear the ominous odor of humans. A few articles of really smelly dirty laundry, left about the garden at night will also deter many wild animals, including deer, raccoons, and rabbits.

® A sulfurous odor can be created by cracking a few eggs and letting set until pungent. The strong scent repels deer.

® Dried blood meal scattered around plants keeps away deer, ground squirrels, rabbits, raccoons, and woodchucks.

® Hot peppers, garlic, vinegar, and water mixed with a squirt of dishsoap and pureed in a blender deters large nibblers as well as insect pests from tasting any garden fare on which it has been sprayed.

® Ammonia. Ironically, the nasty smell of rags soaked in ammonia repels skunks and rats.

® Beer. Set out a shallow tray of beer to lure and drown slugs. To be truly frugal, use cheap beer.

® Repellent plants. Gopher spurge, (Euphorbia lathyrus) repels gophers, with varying degrees of success. Castor oil plant, which is highly toxic, also repels them. Both have some effectiveness against moles. Plant garlic, onions, or ornamental alliums to deter woodchucks. Plant garden rue to discourage cats.

For the most part birds are very beneficial to the garden. They are wonderful insect predators, especially in the spring when they need a supply of protein to feed their young. But hungry birds also can take a toll on freshly sown seeds, tender seedlings and luscious fruits and berries. You may need one or more of the following controls:

For the most part birds are very beneficial to the garden. They are wonderful insect predators, especially in the spring when they need a supply of protein to feed their young. But hungry birds also can take a toll on freshly sown seeds, tender seedlings and luscious fruits and berries. You may need one or more of the following controls:  The use of beneficial organisms in the home garden is hardly new. If you think of Adam and Eve as the original garden pests, look at the effectiveness of one snake. Actually, snakes are wonderful, free rodenticides. They patrol for ground-level mice, shrews, bugs, and slugs. In return they need an accessible water source, maybe a nice, flat rock on which to sun themselves, and not to be run over by a lawn mower.

The use of beneficial organisms in the home garden is hardly new. If you think of Adam and Eve as the original garden pests, look at the effectiveness of one snake. Actually, snakes are wonderful, free rodenticides. They patrol for ground-level mice, shrews, bugs, and slugs. In return they need an accessible water source, maybe a nice, flat rock on which to sun themselves, and not to be run over by a lawn mower.  Many states set up regular hazardous waste pick-up stations at designated times and places. Always dispose of unused pesticides, as well as paints, solvents, and other chemicals, at designated stations. Most disposal sites provide an exchange service on site. If you need a pesticide or other chemical, you can pick up someone else's castoff for free. Contact your local state department that handles hazardous waste disposal for details of procedures in your area.

Many states set up regular hazardous waste pick-up stations at designated times and places. Always dispose of unused pesticides, as well as paints, solvents, and other chemicals, at designated stations. Most disposal sites provide an exchange service on site. If you need a pesticide or other chemical, you can pick up someone else's castoff for free. Contact your local state department that handles hazardous waste disposal for details of procedures in your area.

Sometimes a barrier isn't the answer. You wouldn't want to drape a cover over a rose bush or shimmy up an apple tree with a bolt of cheesecloth. There are situations when you need to spray a pesticide.

Sometimes a barrier isn't the answer. You wouldn't want to drape a cover over a rose bush or shimmy up an apple tree with a bolt of cheesecloth. There are situations when you need to spray a pesticide.  One of the best methods to prevent insect damage is physically preventing bugs from touching plants. Several methods work well depending on the plant and the insect. All methods mentioned are very effective and reasonably inexpensive when done properly.

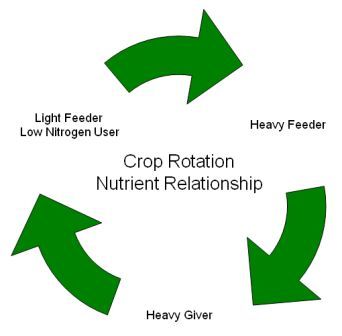

One of the best methods to prevent insect damage is physically preventing bugs from touching plants. Several methods work well depending on the plant and the insect. All methods mentioned are very effective and reasonably inexpensive when done properly. Many diseases and soilborne insects that attack plants remain in the soil even after you harvest the crop. They wait there to reinfest susceptible plants. If you plant the same crop or a closely related one in that site a disease or insect will probably attack the new planting. Prevent this needless loss by rotating your crops each year. The practice costs nothing and could save a lot.

Many diseases and soilborne insects that attack plants remain in the soil even after you harvest the crop. They wait there to reinfest susceptible plants. If you plant the same crop or a closely related one in that site a disease or insect will probably attack the new planting. Prevent this needless loss by rotating your crops each year. The practice costs nothing and could save a lot.  It is the nature of disease organisms and pests to take the easiest route. What could be easier than moving down a row of your favorite host plants and attacking one after the other of them? Organic gardeners have known for generations a way to confound many pests, especially those that prefer one particular crop over others, and it doesn't cost a cent.

It is the nature of disease organisms and pests to take the easiest route. What could be easier than moving down a row of your favorite host plants and attacking one after the other of them? Organic gardeners have known for generations a way to confound many pests, especially those that prefer one particular crop over others, and it doesn't cost a cent.  The first line of defense is to kick the competition when it's down. Don't allow weeds to get a foothold. Not only are they unsightly, weeds are real enemies of any gardener. They rob the soil of water and nutrients meant for cultivated plants. Many harbor diseases or serve as alternate hosts for pests. If allowed to grow, they may shade plants from sunlight, block air circulation around foliage, or crowd out crops entirely.

The first line of defense is to kick the competition when it's down. Don't allow weeds to get a foothold. Not only are they unsightly, weeds are real enemies of any gardener. They rob the soil of water and nutrients meant for cultivated plants. Many harbor diseases or serve as alternate hosts for pests. If allowed to grow, they may shade plants from sunlight, block air circulation around foliage, or crowd out crops entirely.  So much of the information already discussed contributes to your plants' overall health. The best site, proper planting, and transplanting, using resistant varieties, adequate watering, drainage, and nutritional support all help keep plants in optimum condition. Healthy plants have an edge. They are less susceptible to physical stress, attack by disease, or infestation of pests. In fact, studies show insects recognize and prefer ailing plants.

So much of the information already discussed contributes to your plants' overall health. The best site, proper planting, and transplanting, using resistant varieties, adequate watering, drainage, and nutritional support all help keep plants in optimum condition. Healthy plants have an edge. They are less susceptible to physical stress, attack by disease, or infestation of pests. In fact, studies show insects recognize and prefer ailing plants.  Many gardeners buy compost starters to get a pile fired up. These are basically high-nitrogen products that may or may not work, depending on what else is in your pile. Fresh green weeds, with a little soil clinging to their roots, or a shovelful of soil or compost, tossed at intervals into the pile will suffice. But for a great, cheap pile activator, try alfalfa. Toss in handfuls from bales (old or rained-on bales are the cheapest) or use an alfalfa meal product. Horse feed, rabbit food pellets, even some brands of cat litter, are almost pure alfalfa meal.

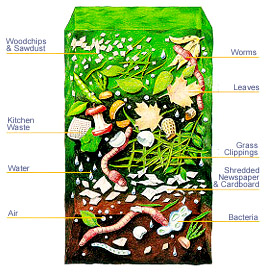

Many gardeners buy compost starters to get a pile fired up. These are basically high-nitrogen products that may or may not work, depending on what else is in your pile. Fresh green weeds, with a little soil clinging to their roots, or a shovelful of soil or compost, tossed at intervals into the pile will suffice. But for a great, cheap pile activator, try alfalfa. Toss in handfuls from bales (old or rained-on bales are the cheapest) or use an alfalfa meal product. Horse feed, rabbit food pellets, even some brands of cat litter, are almost pure alfalfa meal.  You can make composting as easy and cheap as that leaf-dropping tree. All you need are the ingredients and as much time as you are willing to devote to the project.

You can make composting as easy and cheap as that leaf-dropping tree. All you need are the ingredients and as much time as you are willing to devote to the project.  The good news is that anybody can make compost. Actually, compost will make itself without anybody. Consider a maple tree near a fence line. Each year it sheds its leaves, and some of those leaves are blown against the fence where they pile up. In time, the bottom layer of those leaves is no longer recognizable as leaves, but transformed into a dark, sweet-smelling, crumbly soil.

The good news is that anybody can make compost. Actually, compost will make itself without anybody. Consider a maple tree near a fence line. Each year it sheds its leaves, and some of those leaves are blown against the fence where they pile up. In time, the bottom layer of those leaves is no longer recognizable as leaves, but transformed into a dark, sweet-smelling, crumbly soil. Let's answer this question not only from a frugal point of view, but from that of plant health and a healthy global environment as well. Yard and garden waste account for 17 percent of the trash that finds its way into our landfills. Kitchen waste makes up another 8 percent. Combined, kitchen and garden waste account for one quarter of all the garbage we throw out. By composting, you save money used to dispose of waste, including bags and cans, as well as your time spent collecting it. And the environment also wins. You also get the world's best free fertilizer, compost. Not a bad return.

Let's answer this question not only from a frugal point of view, but from that of plant health and a healthy global environment as well. Yard and garden waste account for 17 percent of the trash that finds its way into our landfills. Kitchen waste makes up another 8 percent. Combined, kitchen and garden waste account for one quarter of all the garbage we throw out. By composting, you save money used to dispose of waste, including bags and cans, as well as your time spent collecting it. And the environment also wins. You also get the world's best free fertilizer, compost. Not a bad return.  The method of application depends on the type of fertilizer. Sprinkle granules around the base of plants, scratch into the soil, and water thoroughly to dissolve. Shovel a layer of compost or manure over the soil at the base of the plants, and scratch in with a hoe. This method is called side-dressing.

The method of application depends on the type of fertilizer. Sprinkle granules around the base of plants, scratch into the soil, and water thoroughly to dissolve. Shovel a layer of compost or manure over the soil at the base of the plants, and scratch in with a hoe. This method is called side-dressing.